The following is a lightly edited transcript of my (regular font) conversation with Secretary Hank Paulson (italic font) on the “Straight Talk with Hank Paulson” podcast, released 19 Nov 2020.

Humans are very good at solving problems that are very immediate and where the person who solves the problem benefits from that solution.

Unfortunately, climate change is a problem that manifests itself over decades and centuries, and the benefits accrue to basically everybody but the costs accrue to whomever is reducing the emissions.

Welcome to Straight Talk, a podcast about big ideas from some of the world’s foremost thinkers and doers.

I’m Hank Paulson, Chairman of the Paulson Institute.

Today, I’m speaking with Ken Caldeira.

Ken is one of the world’s leading experts on climate change and currently serves as a climate scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science.

He has made pioneering discoveries in areas such as ocean acidification and energy system modeling and is known to be an out of the box big picture science with diverse interests.

Ken, welcome to the podcast.

Hi, great to be here, Hank.

Ken, I’m really looking forward to our conversation today. I’ve talked with a lot of climate scientists but few of any or as good as you are in big picture thinking. You’re able to put it all together and break new ground in the questions you ask, the areas you study and the solutions you consider.

EARLY DAYS

But before going big, I’d like to go to near the beginning: How did you get interested in science and when did you first develop your strong interest in climate change?

I think my interest in science began when I was a kid, due to the Apollo space program.

The whole “landing humans on the moon” really excited an entire generation. And the reaction to Sputnik by the United States, in creating the Gemini and Mercury and Apollo programs, spurred a whole new thrust in improving education in the united states.

I’m hoping that energy and responding to climate change might have some of the same effect of really revitalizing science and education in the United States. It was these kinds of governmental programs when I was a kid.

But then how did I get into climate science?

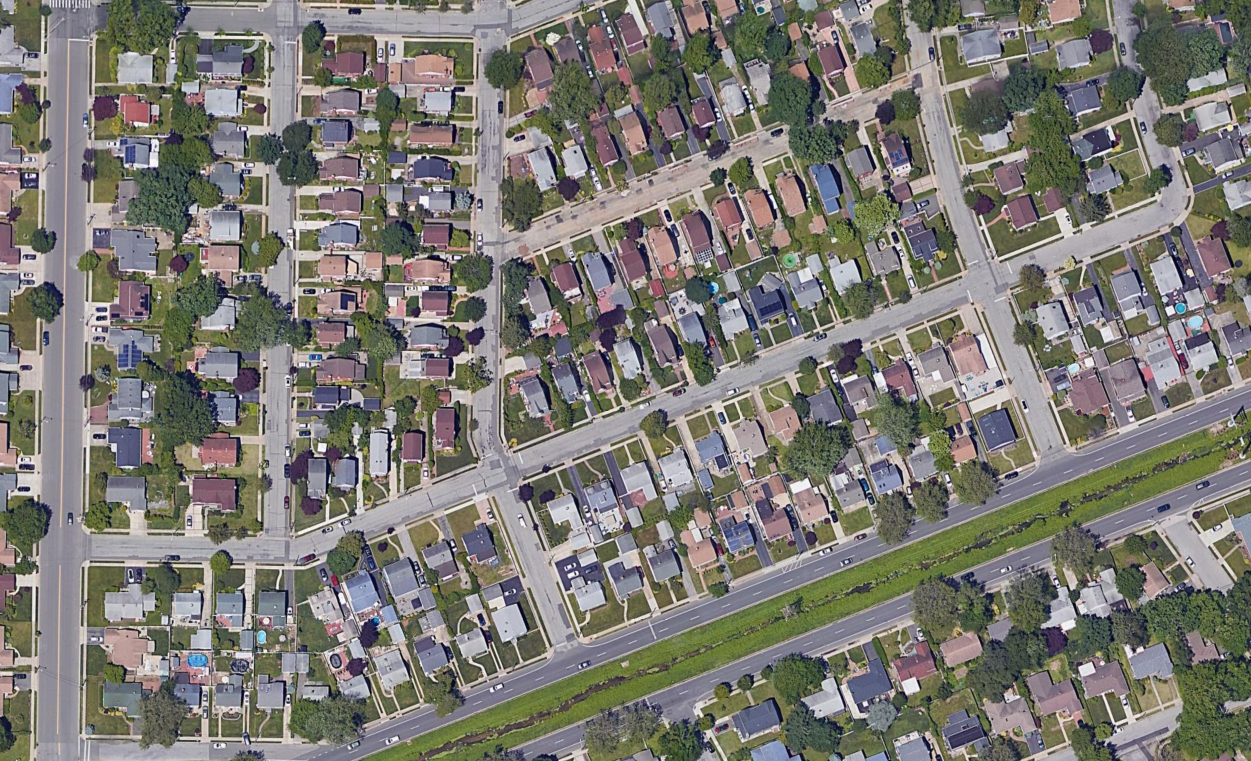

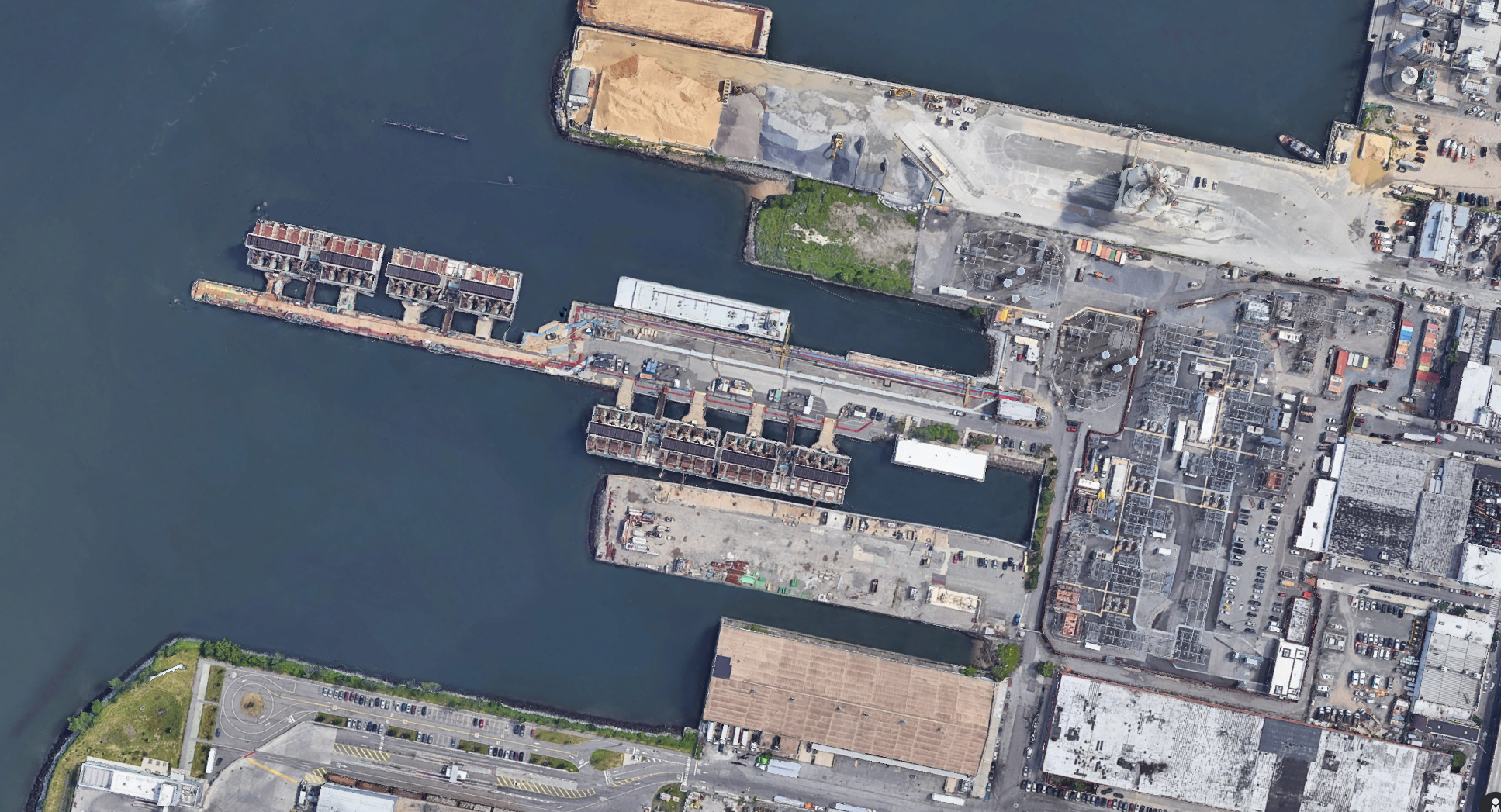

As an undergraduate, I learned computer programming, and [after graduation] was doing software development in Wall Street in the Financial District, basically looking at mergers and acquisitions for places like First Boston and so on.

I remember reading an article in the New York Times. Steve Schneider spoke at a Congressional testimony and also spoke at a [AAAS] meeting and talked about how we might be melting some of Antarctica.

And this kind of blew my mind – the idea that us little puny humans could influence something as big as the Antarctic ice sheet or global climate really surprised me.

And so I just started going back to graduate school in the evenings just for fun to learn about it. And I turned out to be their best student. They offered me a fellowship. I quit my job on Wall Street and the rest is history.

Wow, I tell you, as I have gotten to know over the course of my career, people that are best in class in their various professions, they all have one thing in common, intellectual curiosity. Intellectual curiosity.

And, it’s amazing, I remember Sputnik like it was yesterday. It was just that was huge, wasn’t it? And then Neil Armstrong landing on the moon, Alan Shepard, all that.

It was a fascinating, fascinating, time in our history.

One thing that separates me from most other climate scientists is having spent (I forget what it was) six or eight years working in the financial district in New York because you get a real sense about … . You understand discount rates and you understand competing opportunity costs for using resources in one way rather than another.

I feel that this time in the financial district in New York has informed a lot of my thinking and was very useful.

CLIMATE CHANGE

We’ll get to that in a bit because one of the things that’s impressed me about my conversations with you is you really work to understand the economics of all these uh solutions or potential solutions and so when we get to talking about open air carbon capture and some other things you’re focused on the economic realities and a matter of fact everything you’re doing is grounded in in practical realities how will this work what do we need to do so let’s start with the basic core question how big a challenge is climate change?

There’s two different ways to think about how big the climate change problem is.

One is “Well, what are the bad things or possibly even good things that could happen with climate change?”

But the other is the game theoretic challenge of how hard is it to solve this problem because of its logical structure.

If we look out centuries [and ask] “what are the consequences of continuing in our current modes of generating energy or converting energy for human uses?” [we’ll find] that we’re adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and eventually we’ll melt all the ice sheets and sea levels will go up 200 feet. We’ll be restoring ourselves to the kinds of climate that existed when the dinosaurs were around.

I’m not with Leibniz and thinking this is the best of all possible worlds, but there’s a lot of disruption that comes with this change.

Losing essentially every coastal city in the world is a cost that we don’t want to take on. There are also concerns about crops growing in tropical countries – how it’s already difficult to work outside in the sun in most of the tropics and if it gets hotter and there’s already heat stresses causing reductions in crop yields … . And so, there’s potential for large parts of the tropics to become unsuitable for growing crops and so the risks are very large.

Unfortunately, humans are very good at solving problems that are very immediate and where the person who solves the problem benefits from that solution.

Unfortunately, climate change is a problem that manifests itself over decades and centuries, and the benefits accrue to basically everybody but the costs accrue to whomever is reducing the emissions.

This logical structure, where the costs are borne by people today but the benefits are widely distributed and come mostly far in the future, that’s a really tough problem from a political and economic perspective to address.

We’ve been doing some simulations using integrated assessment models. For the next 60 or so years we’re going to want to invest more in emissions reduction than that emissions reduction will offset in damages.

We’re asking this generation to invest for future generations, and that’s a tough ask.

Yeah. I totally agree that we do best when the crisis is immediate right as opposed to long term, and we also do best when the crisis is national as opposed to global, and this is longer term and global.

But, I want to turn that around a bit, because most of the thinking and it is directed where it should be when we’re looking at the most adverse consequences which are long-term consequences, but there are also some immediate consequences.

NEAR-TERM CLIMATE CONSEQUENCES

Many people don’t understand that no matter what we do today, as a result of the carbon that’s already up there in the atmosphere, there are going to be some very real impacts of climate change some very real shocks in the next decades.

The question I have to you is: How should we look at those? And what surprises are out there that are possible in the next 10 20 30 years? And how should we think about resilience and adaptation preparing to deal with the shorter term shocks?

There’s evidence that global warming is causing storms to become more intense now. We’re also putting more and more infrastructure in harm’s way.

We can expect increased storminess increased flooding, increased heat waves leading to crop failures, and some deaths of vulnerable people.

But what we’re seeing in the next decades is going to be the tip of the iceberg.

Climate change is something that’s cumulative. Each emission basically adds another increment of warming.

If we stop emissions today the Earth doesn’t start cooling for the better part of a thousand years.

Even if we were to stop today, we don’t make things better we just prevent it getting worse.

And it’s extremely difficult to reduce emissions and so the likelihood is for emissions to go up, the amount of warming to go up, the amount of heat waves, floods, severe storms, and so on, going up.

I know that people focus on what’s coming in the next decades in an effort to try to motivate people to do something now but it’s really whatever comes in the next decades is like that’s just like the little tip of the iceberg and what’s really coming down the pike is really gigantic.

Yeah, I agree with you.

People have conflated two things: the “what’s coming in the next couple decades” and “what we need to do in terms of resilience and adaptation with the longer term issue in terms of mitigation”.

We don’t want to ignore what’s coming in terms of where we build and what we do because there are going to be some very real changes immediately and we need to prepare for those. But you’re totally right in terms of where the big risks are.

Most of the climate change that will happen in 10 years from now is already baked in. It’s really only one more decade’s warming.

If you’re trying to deal with the effects of climate change in 10 years it’s adaptation that’s going to reduce that risk.

We need to really get on the program of reducing emissions to prevent the much bigger changes down the road but [in] the near term it’s mostly about let’s build the right kind of infrastructure.

Absolutely. Let’s prepare. Let’s protect our economic security. Let’s adapt. Let’s build in resilience to deal with what’s going to come.

That’s a very, very, different problem from that of avoiding the very worst outcomes which are certain to come unless we act.

SEA-LEVEL RISE

I want to come back briefly to where you started because you read something about the Antarctic ice shelf melting and now a lot of respected scientists are saying that the process of irreversible melting is going on in Greenland and the Antarctic ice shelf. What does this mean in terms of sea rise and over what time period?

The central estimate for Antarctic melting is around an inch a year for the next 10,000 years or so. That’s more-or-less a foot a decade or more-or-less 10 feet each century, which is like a floor of a building.

And so what we’re doing over the next decades is really going to affect people living on this planet for many thousands of years.

ENERGY

Ken, now this is a part of the interview I’m really looking forward to.

What are the things we can do what are the things that science can develop that will let us avoid these or help us avoid some of these most adverse impacts? Talk about science, where science is now, where we need to get. What are the areas where we can have big breakthroughs that make a significant difference?

The main cause of global warming is carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels in our energy system, and that’s both fossil fuels to generate electricity to provide gasoline for cars and jet fuel for airplanes and heat to make steel and aluminum, and so on.

Most analysts now believe that the way to move forward on this is to electrify as much of the economy as possible.

We see this transition now with going from gasoline cars towards electric cars, but electrifying the economy doesn’t do anything if you’re using coal to make that electricity in coal plants emitting the CO2.

The next step is to (the jargon is) decarbonize the electricity system. And that means either basing it on inherently carbon-free technologies like solar power wind nuclear. Or another idea is to burn the fossil fuels and then capture the CO2 and throw that CO2 underground. Now that unfortunately is still expensive.

The cost of solar and wind have come down dramatically. The problem with solar and wind is that you often want electricity when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining and electricity storage is still very expensive.

Wind and solar can penetrate electricity systems a bit now but to really do the entire job with wind and solar we would need much better storage technologies than we have.

There’s a whole suite of different energy system innovations that people are thinking about. There’re other sources of emissions like cement and land use change, but those are less important than the energy system.

That’s a very good summary.

Always when I will talk with people that are looking for huge scientific breakthroughs, I always come back and say to them, “It’s cumulative. Every bit counts whether it’s behavior change whether it’s reducing emissions whether it’s moving to cleaner renewable sources of energy.”

BREAKTHROUGHS

But there also are some very big out of the box ideas that you’ve considered which is: “Is it irreversible the emissions we’ve put in the atmosphere?”

What about you’ve done work on open-air carbon capture talk a little bit about that in terms of what this is what the science is what the economics are how you think about it?

Let me talk about a few of these crazy out-of-the-box things which are fun and I enjoy, but before I do that let me just say, “I like thinking about the big breakthroughs and one of the crazy out of box things that could maybe come in the future … “

We need to realize that if you think about how much solar power got cheaper over the last decade or two, and a lot of that was really Germany putting subsidy on rooftop solar and so on, and the Chinese responding to that by building all of these solar photovoltaic factories, and they just step-by-step increased the efficiency and reduced cost through hundreds of tiny little improvements.

And so, in the case of solar, at least, we saw more-or-less what you’d have to call in aggregate “a breakthrough” that really was the accumulation of a lot of tiny little improvements of learning by doing and so on.

While I’m going to talk about some big breakthrough kind of things we need to remember that a lot of progress comes in a lot of little tiny steps.

Ken, I agree with you totally and I’m a big believer that if we put a price on carbon emissions that we will see incremental steps that will add up and make a big difference.

If we have the right incentives the right regulatory policies the right way to price emissions and pollution will make a huge difference over time. And we never want to take our eye off that ball. And I think behavior changes, but I do think it’s interesting to talk about some of the big ideas.

The danger of course is people will say well maybe we don’t have to do anything because at the end of the day there’s some huge idea that’s going to save us all.

Imagine if it was 1920 instead of 2020.

The things we have today would seem like magic.

Solar photovoltaics – nobody ever thought about that. There was no silicon chip in 1920.

Nuclear power would have been just a science fiction story.

The idea that wind power would come back, that aviation would be big, that we’d have cars all over the place, and …

We do ourselves a disservice by not using a lot of imagination when we think about the future. We just shouldn’t believe our imagination too much. But anyway… so to come up with some of the basic ideas ….

One basic idea is, “Well, if we’ve emitted all this carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, can we go and grab it out of the atmosphere and pull it back out?”

And we know this is possible because plants do it all the time. Plants take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere powered by sunlight and convert it into carbohydrates with chemical energy.

One way you can pull CO2 out of the atmosphere is to grow plants and that’s the whole idea of biofuels and bioenergy and so on. Or you could also potentially bury that biomass. And people have even talked about taking hydrogen from other sources and upgrading that carbon to make aviation fuels based on biomass.

The simplest way to draw CO2 out of the atmosphere is grow plants, but the problem is that plants take a lot of area and are very inefficient. But they are self-assembling little robots, so that’s good.

Various groups, especially one in Switzerland and one based in North America, have developed chemical processing approaches to extract CO2 from the atmosphere. The problem is it’s expensive.

That said, there are some very difficult to decarbonize parts of the energy system. Let’s say you want to fly from New York City to Sydney in an airplane. There’s just no battery that’s light enough to ever power a jet plane like that and so dense hydrocarbon fuels are still the fuel of choice.

The idea is, “Well, maybe you could still use fossil fuels for that long-distance aviation but then have a plant somewhere pulling that CO2 out of the atmosphere.” My guess is it might get used for these kind of niche applications but it’s not going to be the main show.

It’s just too expensive in my judgment.

There’s also sort of crazy out of the box ideas for electricity generation and my favorite one (and this one’s crazy a bit) is …

We did a study looking at the power in the jet streams. These are the those powerful winds that are more-or-less up above where the jets fly.

On a good sunny day you might get one kilowatt of power per square meter [from sunlight] in the middle of a desert in the middle of the day. You can get 10 or 20 times that power in winds in the jet stream.

If we could ever get flying wind turbines in the jet streams there’s more than enough power there to power all of civilization and it’s pretty steady. I don’t know if we’ll see that in the coming decades or even this century but I think sooner or later unless we find something really good like fusion, or something, my guess is someday we’ll tap into the jet streams.

There’s all kinds of ideas. Obviously, there’s a bunch of different nuclear power plant designs and I think nuclear power is something that I think is likely to play a major role in addressing the climate problem.

It’s one of the few technologies that fits into our existing energy system in a relatively easy way.

When solar was expensive, we looked for ways to make solar better and cheaper. I think if we had a concerted effort to make nuclear better and cheaper, it would likely play a major role in helping to address the climate problem.

SOLAR GEOENGINEERING

One idea that does work well in the climate models is this idea of solar geoengineering, of putting particles high in the sky above where jets fly, in the stratosphere, and reflect some sunlight from the Earth.

This in climate models works surprisingly well at offsetting most of the effects of high greenhouse gas concentrations.

It’s one of these things that almost works too well in the models because …

I’m afraid to do it in the real world, but if we actually believe the models and you weren’t worried about socioeconomic and political knock-on risks, just in terms of physical risk reduction, I would think putting aerosols in the stratosphere is probably sensible. But I’m not sure I believe our models enough to do that.

As you pointed out to me when we talked about it in the past it raises all sorts of ethical and political questions: Who would be authorized to do it? How would it be done? And because when it’s done it affects everyone, it is it’s a very controversial subject, but it’s one that scientists need to explore and look at.

As I mentioned earlier, each carbon dioxide emission causes another increment of warming. And so if you stop greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth doesn’t start cooling. It just stops getting hotter.

But, if there’s ever a perception of a climate crisis and people demand that politicians do something to cool the Earth off, solar geoengineering is the only thing they can do that would cause the Earth to start to cool within their terms in office or within their political careers.

I don’t know if ever climate change will ever become perceived as an acute crisis that people need to address now, but if that public perception ever occurs the political pressure on a politician to do something will be immense.

Imagine if you were a leader of a country and you had repeated years of crop failures and famines were threatening your country.

And you thought that by doing a relatively cheap thing and putting some aerosols in the stratosphere, that you could protect the lives and well-being of the people in your country.

I think you would be remiss as a leader not to seriously consider solar geoengineering.

I don’t know what the probability of climate change being felt as an acute crisis is, but if you think that it’s substantially non-zero then you have to say, “Well, look, we’d better understand these solar geoengineering options because the political pressure to deploy them could become intense. And if it’s a really bad idea we better understand that now.”

WHAT PART OF THE CLIMATE CONSENSUS MIGHT BE WRONG?

Let’s move right along here. What parts of the current climate science consensus might turn out to be wrong?

That’s a tough question.

I don’t know if it’s a climate consensus, but I think this question about: “To what extent is climate change going to be a slow gradual progressive thing versus it come in sort of jumps and starts and shocks?”

People talk about climate crisis and I’m just not sure. Climate damage tends to show up locally.

As there’s an extreme storm or there’s a flood or there’s a drought with a crop failure and so year by year, we have different localities that are experiencing crises. But, they’re basically local or regional crises – like Katrina hits New Orleans and maybe there’s disruption to the Gulf Coast, but basically the country’s economy goes on.

And so the question is: “Over the next decades, is it going to continue like that where basically you have a bunch of isolated regional effects and they’re addressed basically on a regional basis, or is it going to be something more like this coronavirus thing where something affects the entire world and the entire world says, ‘oh, we need to deal with this acutely now’?”

It seems like there’s one group that uses words like “climate catastrophe” words like “extinction” and views climate change as this acute kind of global disaster. And there’s another view of it – Well, there’s a lot of series of small local disasters that become more commonplace but at the system level is more of a cost than a catastrophe. It’s a local and regional catastrophe but globally it’s a cost.

I’m not really addressing your questions. I’m not saying it’s false. It’s more like an uncertainty that I don’t know. It’s the same with when I talk about geoengineering.

Will climate change ever be dealt with acutely as an immediate problem or will it always be everybody’s third or fourth or fifth biggest problem?

CLIMATE, ENERGY, AND DEVELOPMENT

Most people, if you’re out of work or if you’re in sub-Saharan Africa, even if it’s a hot day, your problem is not having a job or not having money. There’s other big complicated things about this interplay between economic development and climate change.

If you gave somebody a choice of having three degrees higher temperature but having a full bank account versus being in poverty and in a better climate, a lot of people would take the bank account and the higher temperatures.

This question of: “How do we do both of these things simultaneously of have the world develop and increase people’s economic well-being at the same time that you’re protecting their environment?”

But our whole political systems … most leaders are focused on the short term on their time in office. Sometimes they’re looking a year or two ahead but very seldom are they looking really long-term, so short-termism works against us.

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND POLITICAL POLARIZATION

But I would like to, as we’re talking about politics, I want to end by getting your thoughts on the politicalization of science.

We’ve seen it in climate change. We’re seeing it now with a pandemic. What do we need to do to take the toxicity out of the debate?

Now I’d always thought that when you look at competition, that academics and scientists are the toughest on each other in terms of peer reviews and so on so. I know you’re always going to have, and that’s healthy to some extent, but this has gone beyond that right.

So, what do we need to do? How do we deal with this and How big a problem is it?

Obviously this problem of not having shared facts is really terrible. I had always thought we will agree on the facts and our values will disagree. Then at least we could discuss assuming the same set of facts. That seems to have gone out the window.

I found that a few different things help. One is being willing to consider things like geoengineering and nuclear power — that you’re not coming in with a bunch of filters.

I think another thing that helps is a reiteration of shared goals that if you say, “Most people want a healthy growing economy. They want to see people in developing countries have access to more material goods and services. People would like to protect the environment.” And so [first] some reiteration of shared goals and then you can say, “Okay let’s have a discussion about how to attain these goals, and how to balance competing interests.” I think entering into the discussions and showing a willingness to be flexible [helps].

Too often in Washington, people personalize. If you disagree with someone in their position, too often people attack them and to attack their motives or go after them personally, rather than dealing with the facts.

But in any event, I think that’s a good note to end on because science is so critically important to our way of life and as you pointed out we’ve had so many breakthroughs over the last hundred years.

And we’re going to continue to have major breakthroughs if we move forward in the right way, so, Ken, thank you very much for joining us today and I greatly appreciate it.

Well, thank you for this opportunity

You have listened to Straight Talk with Hank Paulson, a podcast of the Paulson Institute.

To find more episodes from leading thinkers and doers please, visit paulsoninstitute.org/straighttalk or download on Apple, Google Play, Spotify and Stitcher.

And don’t forget to rate and subscribe.

Thank you for listening and see you next time.