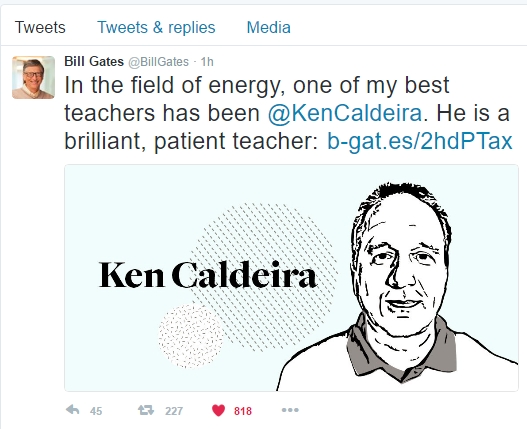

I was pleasantly surprised to read Bill Gates calling me ‘my amazing teacher’ on his GatesNotes blog and calling me ‘brilliant’ in a tweet:

It is very nice to be called ‘my amazing teacher’ or ‘my brilliant teacher’ by anyone. It is especially nice to have those words said about you by Bill Gates.

The curious thing is that I don’t feel like I have taught Bill Gates much of anything. For the last decade or so, a few other people and I have been running a series of learning sessions for Bill, bringing in experts on different topics related to climate and energy. All I have done is help expose Bill Gates to some information. He is a self-learner, and generous enough to attribute his self-learning to the people around him.

The thing that I have learned the most from interacting with Bill is to value my time and use it thoughtfully.

I have never seen Bill Gates try to multi-task. I have never seen him check his text messages or email in the middle of a meeting. He does one thing at a time and gives that one thing his full attention.

Bill is limited by resources in many of the big things he wants to accomplish: eradicate diseases, bring prosperity to the poor, solve the climate / energy problem, etc. However, in terms of personal consumption, Bill is not limited by money. He is limited by the amount of time he is willing to allocate to an activity. For Bill, time his is his most precious resource. And he thinks very carefully about how to allocate his limited time.

If time is Bill Gates’s most precious resource, maybe it is my most precious resource as well.

One of the things that is great about Bill is that he takes time to read. He usually reads at least one non-fiction book each week. Here is the richest man in the world, who can allocate his finite time to any activity he wants, and the best thing he can think to do with his time is sit in a chair and read.

When people think about the lifestyles of the rich and famous, maybe they think of wild beach parties in Bali. However, sitting in a chair and reading a good book is also part of the lifestyle of the more intelligent of the rich and famous. And I can partake of the lifestyle of the rich and famous simply by buying a book and sitting in an easy chair and reading.

Why don’t I read more? Is it because of the cost of books? No. The amount of time I spend reading is limited primarily by my willingness to allocate time to that activity.

My mom lives in a retirement community. She brings a kindle with her when she has to stand on line in the cafeteria so she can read while she waits to reach the steam tables. She asked another person on line why he was just waiting without doing anything else. The man replied, “What does it matter? I’m retired. I have all the time in the world.”

My mom responded, “What do you mean? You’re in your 80’s. You don’t have much time at all.”

My interactions with Bill have taught me that money can relieve constraints, but even with those constraints relieved, we need to ask ourselves the question: “How do I want to allocate my time? What do I want to spend my time doing?”

Yes, we are more constrained than Bill Gates, but we all have time that we can allocate more wisely. Money opens up possibilities, but we can all be choosing better among the possibilities that are already open to us.

I remember, as a kid, spending whole summers playing Monopoly with my friends, and these summers seemed to last forever. Perhaps the last time that time seemed infinite was playing bridge with my friends in college. Time then wasn’t zero sum. There would be time enough for everything. I look back fondly on that feeling of time abundant.

As one progresses through life, it becomes clear that time is very finite. Time is in short supply and there will not be time enough for everything.

Time is our most precious resource, and we must learn to use our time wisely.

This is what I have learned from Bill Gates.